Star guts. Ground mountains. Seething motion unseen. Organism detritus. Feculence. Bug poop.

_____

Knees pop as I bend down and pinch a gram of soil between my fingers. I bring it up to my face: grains, and the filler between the grains. I am looking at 1013 bacteria, each a tiny furnace eating chemical energy.

nutrients: carbon, nitrogen, phosphorous, potassium, calcium, magnesium, sunlight.

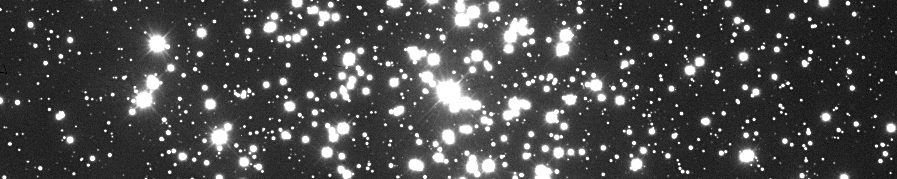

The critter universe in this quarter of a thimble of soil is more numerous than the stars swirling around the spiral galaxy we call home. By a factor of roughly a hundred. Or 1,500 times more numerous than the people on Earth. I work with such numbers every day. After thirty years, I still cannot fathom their import. Grains escape my clumsy dermal trap and sift back down, to the ground.

soil: earth, terra, qaḏāra, drytt. (The word dirt , from Middle English drytt, annoys soil scientists; it is an epithet.) Clay, silt, sand. Browns and tans, flecks of blacks and reds and whites. Crystalline facets sparkling in bright sunlight.

_____

Soil is Earth’s largest reservoir of carbon, the basis of all known life. Too much carbon in the air, and we die, we voracious eaters and stirrers of dirt. Too little, and we die, we profligate disturbers of Nature. We live, we stumble, we contemplate, among a balance of energies that flow in overlapping cycles, large and small, short and long—a balance that seems ever more fickle, precarious, as the world grows warmer.

_____

I look up and squint. The Sun, a middling, middle-aged star in an unremarkable part of the galaxy, warms my face, the skin on my arms. I know this sensation to be my brain, some still poorly understood interconnected agglomeration of neurons, synapses, and neurotransmitters, making sense (or such is my perceived reality) of neurochemical signals instigated by infrared quanta, packets of energy that were born of violent subatomic interactions and that fled the core of our star a thousand millennia ago. It takes that long for light to wend its random way from the Sun’s core to its surface.

macrofauna: woodlice, worms, beetles, ants.

A roundworm has 300 neurons and several thousand synapses. My cat has three-quarters of a billion neurons, and about 1013 synapses. She is gray and feisty and adorable, and getting on in years, like me, but she is not the sharpest knife in drawer, perhaps also like me. I rub a larger number of bacteria between my fingers than she has synapses, the connections between her brain cells.

mesofauna: mites, nematodes, roundworms, coneheads, blind and heartless pauropods, indestructible tardigrades.

_____

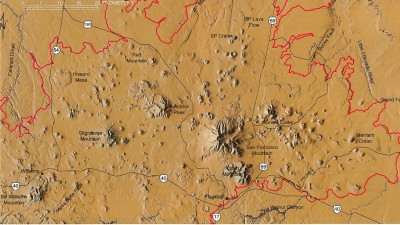

Digital elevation model of the San Francisco Volcanic Field in Northern Arizona. (source: AZGS, click to enlarge)

I wonder, where was this microcosm of mineralogy, pinched between my fingers, a million years ago? Flagstaff sits atop the San Francisco Volcanic Field, a complex of around six hundred volcanic cinder cones that have been active over the past six million years. The San Francisco Peaks, named in the 17th century for St. Francis of Assisi, themselves are the weathered remains of a stratovolcano that erupted between 0.4 and 1 million years ago. This bit of soil, at least its silica grains, may very well have been in the upper mantle, squeezing towards a volcanic hole in the Earth’s crust, when the photons warming my skin began their arduous journey.

_____

We know about the bacteria in this pinch of soil, at least their rough numbers if surprisingly little else, because our optical instruments, microscopes, allow us that determination, given enough time and persistence.

microfauna: bacteria and fungi, thousands of species, mostly unknown to science; yeast; protozoa with their pseudopods, their flagella, their cilia; disintegrators of organics.

I don’t see stars in the daytime sky, other than our Sun, but I know they, too, are there, each of them a furnace converting matter in their cores to energy. At night, our telescopes show us their rough numbers, given enough time and persistence. Our microscopes also enable us a rough count of our neurons, and our synapses, these tangled little engines of thought. We don’t yet understand consciousness, our self-awareness that causes us to ask questions, stir the soil, and build tools so we can determine these incomprehensible numbers, and to ponder—if not grasp, for that seems a long way off still—their significance.

Comments

On Dirt — 6 Comments